The Honduras Mission, Part I

Field Notes II.XXX: Supporting and photographing a mission trip to Nacaome, Honduras in July 2024

Welcome to Field Notes!

Why is it that journeys always seem to begin in the dark of night? The obvious answer is that trips are long, flights leave early, and we must be prepared for waits and delays. I can see some more mysterious forces at work, though. It is as if the fates are preparing us for the unknown ahead by ripping us from our routines and pushing us into the day with eyes already open. It is Wednesday July 17, 2024 and my alarm wakes me at 3:00 am.

I arrive at Pastor Luis’s home by 4:00, the only one with lights on along the quiet street. Luis is pastor of The Bridge Community Church in Athens, Ga. For the second time, he has coordinated a mission trip to Nacaome, Honduras together with a local mission trip organizer, Suzanne. The goal is to support a small school and help construct a home for one of the families. My son initially agreed to help with this trip. However, after a conflict arose with his upcoming entrance into college I was offered his spot instead. So, I find myself here sleepy eyed, with a backpack filled with more camera gear than clothes and ready to step off towards terra incognita.

Angela arrives a few minutes later. She is a native Spanish speaker and works with the Hispanic ministry at the church. We load in the car for a long but smooth ride to the Atlanta airport. Making our way steadily through check-in and security, we arrive at the gate. Here we meet up with the rest of our crew, Todd and his daughter Stephanie and Andrea and her daughter Peyton.

Several years have passed since I last flew in an airplane. I stare in fascination at the earth falling away below. Clouds spread out far and wide above the textured green landscape. It looks like pilled fabric on worn microfleece and floats by as if in slow motion. The flight is a short 3 hours. Feeling almost too soon, I find myself on the ground in a foreign land in the town of San Pedro Sula.

Before leaving the airport we exchange our currency with a shifty eyed man in a small, very unofficial appearing booth. Angela watches like a hawk to make sure we aren’t getting ripped off. Still, I notice that my multiplication factor is 23 vs others’ 24. Apparently this is due to my smaller bills. I am in no position to question it, so I let it go.

A crowded bottleneck at the exit of the terminal leads to the parking lot. Here for the fist time I am directly struck by the heat. Sweat beads on my forehead as we wait for our transportation. Distant mountains on the horizon draw my gaze. They stand ominously and with a mysterious allure, draped in dense, hazy air.

We pile into a van barely large enough to contain the 7 of us, plus our driver and Henry, our local host. I hold on to my pack, but the rest of the luggage is strapped in the bed of a tiny pickup truck that follows us as we begin our journey southward.

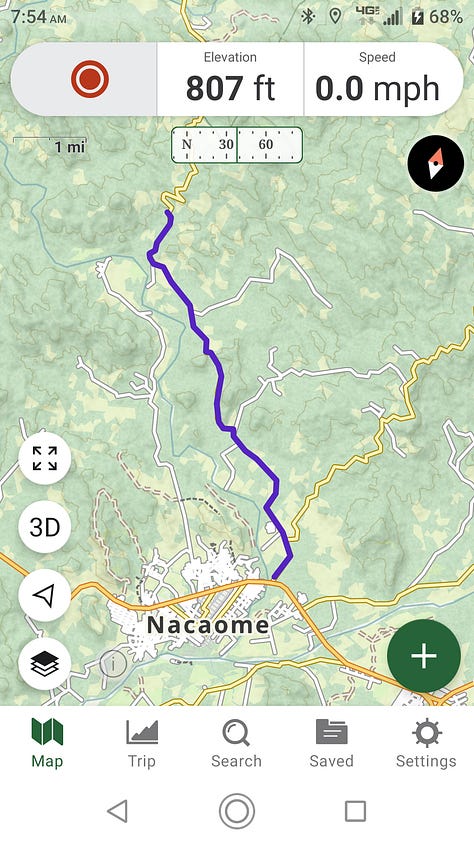

The drive to Nacaome is about 4 or 5 hours, almost directly south through Honduras. We start at the edge of the Caribbean Sea and by the end are near the Pacific Ocean. In between, we travel along a small highway defined by contrasts. Villages of various sizes consist of buildings ranging from chain fast food restaurants to piecemeal shanties. Hungry cows and stray dogs meander along the shoulders while small fruit stands offer plantain, dragon fruit, and tamarind. We dodge and swerve amongst traffic, communicating our presence with beeps and honks, as an ox-drawn cart quietly plods along the shoulder.

The road climbs from low lying sugar cane fields to dry mountain passes covered in pines. Pre-industrial agriculture stretches beyond the patchy areas of development along the highway. Beyond that stand the ever present green mountain peaks.

We stop for a brief lunch of fried fish and plantains along the shores of the sprawling Lake Yojoa. From there, the drive continues through the late afternoon. Directional light from the lowering sun shines through the clouds, illuminating the varied shades of green on the mottled hillsides. As sublime as this appears, I can only see it through the tinted side windows of the van.

The journey continues and the hours slide by with the blurry roadside sights until we wearily roll through the town of Nacaome. The main road here is wider and cleaner. A massive new bridge is under construction. These are recent government initiatives to approve appearances in the area.

Our accommodations are just passed the city, in a small gated neighborhood. The four ladies will stay in two rooms in a blue rental house. Separated by one house in between, I am to share a room with Todd in a second house. Pastor Luis is in another room and a third room is for Suzanne, when she arrives separately.

We convene at the ladies’ blue house for dinner. An older woman named Roxie lives here as well, and she prepares all of our dinners and breakfasts while we are here. Tonight we have delicious chicken taquitos and are introduced for the first time to Honduran drinking water. This water comes in square-ish plastic bags containing half a liter each. Common practice is to simply tear off a corner with your teeth and drink the water directly from it.

I take a couple of water bags back with me to the house I am staying in. The tap water is not even safe for brushing teeth. A shower, however stuttery from a dysfunctional shower head, feels wonderful. Then, with the room’s air conditioning set to high, it is time for sleep.

The time change gets me. It is 2 hours earlier in Honduras and my eyes pop open at 3:00 am. The room is uncomfortably cold, but only because I don’t have a blanket on my bed, just a sheet. I put on pants, socks, and a long sleeve shirt and manage to sleep again until about 5:30.

I tear the corner of a water bag and empty it into the smaller of my two water bottles. Its the perfect size for the packets of instant coffee I brought. Cold instant coffee from a plastic bottle. It tastes about as good as it sounds, but as I sip it I feel like a master of survival.

Henry is up and the house is open, but the outer gate is still locked. I explore the yard with my camera and 50mm prime lens. Soon it is time to walk to the blue house for breakfast. Along the way I pause to photograph a flowering bush at the house in between. The elderly lady living there comes out, eager for a greeting, and she patiently allows me to capture her portrait.

Breakfast includes homemade eggs, tortillas, beans, and plenty of hot coffee. Now I feel prepared for any challenge the day puts before me.

By 8:00 the group is ready to start on our day’s adventures. A full sized school bus has been reserved to transport us and awaits on the roadside outside of our compound. With windows down and plenty of room for all, we start in the direction of Nacaome.

Before reaching the town, we turn north on a small, rough road. The first few hundred yards are in the process of being paved. After that, we crawl along an entirely dirt road that jars us harshly with its pits and ruts despite our slow speed.

We wind thought the green countryside. Cows, chickens, and an occasional horse lazily gaze at us as the bus rumbles by. One moment we pass a brightly colored villa, walled and fortified. Minutes later, we drive past the barest of shacks that could be called a residence.

The climate here looks drier than a jungle. Venerable fences line the roadway and fields. Some stretches consist of sun bleached wooden stakes holding up rusted barbed wire. Others are dark walls of stacked rock. All are slowly being reclaimed by the grasp of verdant vegetation. How many generations ago were these fences built? And, by whom?

Trucks loaded with passengers in their beds pass us in the opposite direction. Other vehicles overtake us, kicking up clouds of dust as they go. I kneel in the seat towards the back of the bus trying to view the jagged hills surrounding us, and bang my head on the window several times. In all, the road is 6.2 miles long, but takes over an hour to traverse its length.

Our long drive ends at a fenced dirt driveway leading up a hill. This is the school for the community of Casa Nueva. In anticipation of our arrival, the children are all lined up at this entrance way. Each of our names is printed colorfully on a piece of paper held up by a child. The little girl holding the sign with my name takes me by the hand and escorts me up the hill. Two bare buildings, open to the air and without power, stand in a clearing near the top. In front of one of these buildings we are all seated in a row of chairs for introductions and a presentation. Later, one of our group mentions how significant the printed signs of our names are. There isn’t a computer or printer within miles of here.

The new director of the school speaks to us briefly, translated by Angela. Then comes a performance. The kids have rehearsed their national anthem and sing it for us. Afterwards, we are asked to sing ours. So, we stand and we sing.

Andrea, Angela, Stephanie, and Peyton immediately begin engaging and bonding with the children. The boys play with a soccer ball in the yard, while the girls gather flower bouquets as bright as flames, offering them to Peyton and Stephanie.

The school has three toilets, but none are working. One is clogged, the other dislodged, and the third bowl is broken. Todd has a background in construction and has a lengthy discussion on what it would take to fix the problem.

The time comes for us to go to the location of the house we are here to help build. Very close to the school on the other side of the roadway, another uneven driveway drops down the hillside. Here, on a level patch of dirt, stands the structure where the family lives.

The current house is a shack framed with scrap pieces of wood and sticks. The walls are black plastic sheeting and a rare piece of corrugated tin. A husband and wife, two small boys, and a grandmother live here in a space not much larger than a standard bedroom. Several skeletal dogs and a tiny kitten with glittering eyes slink through the yard.

Adjacent to the shack, work on the foundation of the new house has already begun. Deep trenches for the footings of the walls have been measured and dug. A small amount of concrete and rock has been placed in the trenches, but our first task is to mix more concrete, wheelbarrow it to the trenches, and dump it in.

The concrete mixing takes place on the ground, under the full impact of the mid day sun. Wheelbarrow loads of gravelly sand are roughly mixed with bags of concrete powder by digging and turning the material with shovels. We are taught to form this into a ring and water is dumped into the middle. Then, carefully, concrete mix on the outside of the ring is shoveled to the inside. Slowly, the diameter of the ring narrows as the concrete develops a muddy consistency. All of this then gets turned and flipped until it has an even wet pliability.

The effort of shoveling in the sun and humidity is intense. The sun shirt I am wearing is entirely soaked through with my sweat. Sun shirt. In this heat I wear a long sleeved, hooded, sort of breathable sun shirt. The thing is, partially due to my oversight and partially due to a dysfunctional healthcare system, I was not able to get prophylactic malaria mediation before the trip. The good thing is that there isn’t an active malaria outbreak right now. There is one for Dengue Fever, but no treatment is available for that one. Either way, I am not going to risk getting bitten by mosquitos and the best way is to keep covered up. Oh, and I won’t get sunburned, either.

The shoveling and wheelbarrowing continues. We work as much as we can, but none of us are conditioned to this level of heat. I go until I am lightheaded and then, still hot in the shade, am covered in goosebumps. I suck water from bags like a plastic vampire, but it as soon as the water goes into my mouth it pours right back out through my skin.

At lunch time, I am more grateful for the longer break than for a meal. The carb laden diced potatoes in tomato sauce on crispy fried tortillas are unfamiliar but delicious. Despite their flavor, hot food in a hot environment is challenging. After lunch settles, it is back to work shoveling and sweating until 2:00 pm.

Todd begins to recognize our group’s limitations in these conditions. He asks questions about how to make the process faster or more efficient. Before long there are loose plans to hire additional workers to help during the week.

As our work concludes at the site for the day, we tiresomely drag ourselves up the hill to the bus. I settle into my damp clothes in a back seat, continuing to perspire until the bus begins to move and generates a weak breeze.

Shaken as we are on the bumpy ride back, the down time allows us to recuperate. Before returning to the houses, however, we drive into downtown Nacaome. The bus can only take us so far on the narrow streets, so we walk a few blocks to a small, nondescript hardware store recessed from the roadway. Here Todd is able to purchase a new toilet bowl for the school, cement for it, and a new shower head for our house. All of this for the equivalent of about $10.00.

Night settles in earlier here. Cleaned and cooled in our rooms at the houses, we finish another wonderful meal at the blue house and spend time reflecting on the day. It is dark as I slowly walk back to my house and air conditioned room. I look forward to quickly falling sleep. And then, doing this all over again tomorrow.

Hey everyone, this was a long week but wow, did it fly by! I’m not going to drag the experience out by doing a post for each day of the trip. Instead, it will be a three part series and hopefully by then I’ll have a film of the trip completed. The posts may be a little long and photo laden, but I hope this is a good compromise.

Have any of you ever been to Honduras? Have impressions or questions about things I didn’t cover fully? Let’s get into it in the comments!

Are you getting something out of Field Notes? Help me make it better! You can do this by sharing, subscribing, or supporting with a paid subscription.

Great story and photos Erik - sounds like tough going!

The shovelling and wheelbarrowing would have been hard enough.

But instant coffee made in a bottle of lukewarm-cold water? Ouch.